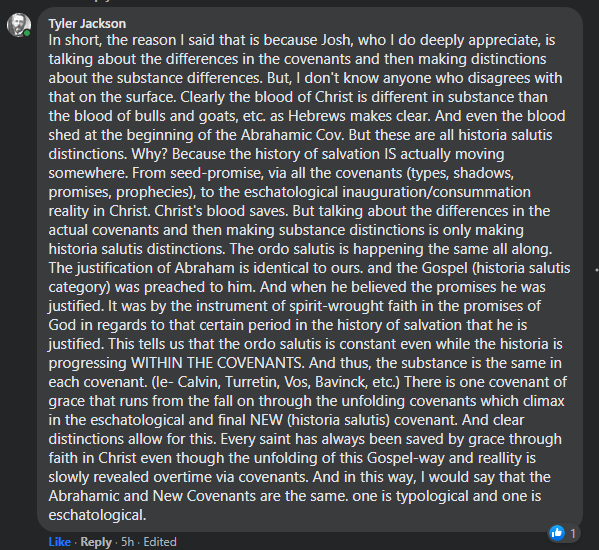

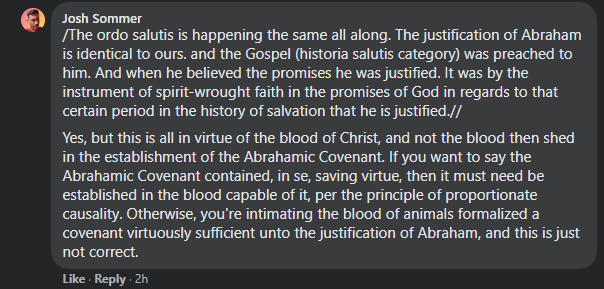

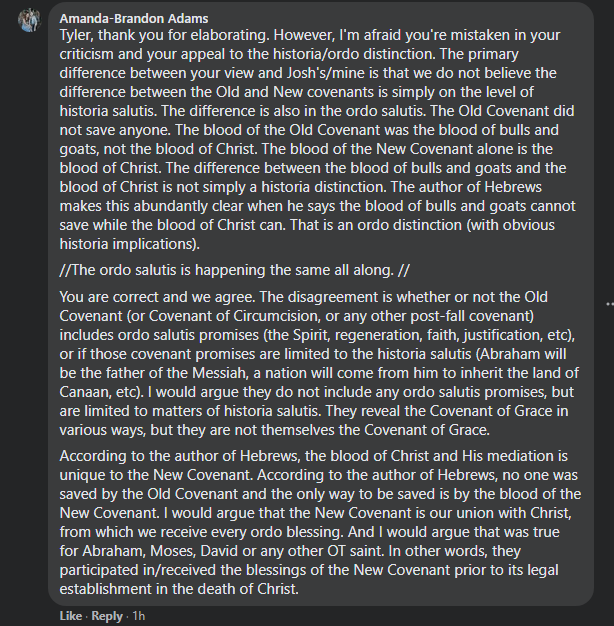

This is a public response/interaction to the comments made below by Pastor Tyler Jackson, Pastor Josh Sommer, and Mr. Brandon Adams. Josh and Brandon are responding to Pastor Tyler Jackson. I initially considered posting it as a comment but decided it would likely be even better to record it here as a response where it can be referenced and have a wider reach over time. You might ask why I am responding if they’re not addressing me. That’s a fair question. I was initially a part of the conversation, which is on Josh’s facebook page, and in fact the thread is under my initial comment. I stepped away because of work and because I was disappointed with Pastor Josh’s last response to me, where he engaged in an ad hominem attack and misrepresented my reply. So my response is not totally without warrant. More importantly, I am posting it here in hopes that it will profit others. Do read the comments of each of these men—Tyler, a classic Westminster Federalist, as well as Josh and Brandon, both 1689 Federalists. Doing so will establish the context for my response below.

My Response (Impromptu)

The blood of Christ shed temporally in space, time, and history is unique to the New Covenant. It is not new or unique symbolically, and therefore spiritually, but is present and exhibited from Genesis 3:21 forward. Thus, Able offered an acceptable sacrifice in Genesis 4:4, by faith per Hebrews 11:4, following God’s institution of such in Genesis 3:21—this is spirituality, not carnality, although “carnal” means were employed to express and reveal said spirituality. Christ’s work is thus symbolically, and therefore spiritually, represented here in Abel’s worship which, again, follows God’s own institution. I remind you that the NT is no different: Christ was incarnated (carnal/physical) and lived in perfect obedience by faith and died as an incarnate man whom we are joined to by faith (spiritual), having fulfilled (antitypical) all that was pointing to him (typical, which is based upon the symbolical) from the OT.

Tyler’s critiques are on point. No one argues that the blood of an animal in itself was efficacious. No one. So we agree that the sacrifices were carnal. But we disagree, and we disagree strongly, that they were merely carnal for then-present saints. That cannot be defended for a moment. Rather, the sacrifices were (1) carnal, (2) symbolical [and therefore religious and spiritual], and (3) typological. You can’t admit 3 and deny 2; therefore, 2 is admitted where 3 is admitted, which any sensible person would admit 3 is present all over the OT. You can’t admit 2 and deny inherent spirituality because that’s 2’s whole purpose, to teach of religio-spiritual truths; therefore, things being merely carnal is not possible because spirituality was present. Now, every person in the OT seeing or embracing these truths is another question. Obviously, not all did. If you have read Fairbairn and/or Vos, you understand this. 2 is the only thing holding back 3 from devolving into mad allegory. 2 is also the only thing that gives OT saints meaningful worship which we must not deny them.

Symbolically considered, then, the sacrifices were efficacious, exhibiting religio-spiritual truths embodied in the sacrifices themselves and later fulfilled in Christ to be embraced by faith, and thus they ministered to the saints of that time, which means they contained then-present religio-spiritual value and were mediums for religio-spiritual expression. Which may be what Josh and Brandon are saying. Maybe not. I doubt it because their position is that things were merely carnal. But, if merely carnal, there is no meaningful worship which the OT saints could have engaged in. So why in the world does the Lord rebuke them in Amos 5:21ff? Why would Moses call Israel to circumcise their hearts? And how could God accept Abel’s sacrifice? Not possible if merely carnal.

But here the 1689 Federalist will say, as Josh and Brandon already have, that the Old Covenant did not and could not effect salvation in itself. But of course! This should not surprise us. But neither should we treat it as if it’s a problem unique to the Old Covenant, because, the New Covenant, abstracted from spirituality, does not effect salvation either, i.e. simply reading Scripture or hearing it preached or receiving baptism or partaking of the Lord’s Supper do not, in themselves, create or nourish spiritual life. The problem of dead-letterism, ritulaism, and dead mechanistic motions is a problem that exists in both testaments. We are not Roman Catholics. We do not believe in ex opere operato, either under Moses or Christ. Thus, neither under the Old Covenant or the New is anything effectual apart from the Holy Spirit working, nor do any elements of worship in either covenant minister to the members in any truly beneficial way apart from faith and understanding. So the problem is not really a problem unique to the OC. And anyone who says otherwise needs to read John 14, John 15, Romans 11, the Hebrews warning passages, and the warnings to the Revelation churches again. After all, where, pray tell, are those Revelation churches which Jesus warned?

The issue is that Josh and Brandon want to have the substance of Christ present, by way of being “revealed” but not present in the very nature of the OT covenants or the OT sacrifices, which is where the so-called revelation took place, historically speaking. Hence, Tyler’s point about historia/ordo distinctions. So which is it? 1689 Federalists can’t have their cake and eat it too.

Either the OT saints were saved, and therefore there was spirituality and meaningful worship present in that Christ was symbolically represented even though his human blood had not yet been shed temporally and even though not all covenant members recognized or embraced this, or, spirituality was absent and therefore Christ was absent and they were therefore not saved. Pick. Now as soon as federalists admit the former, their scheme, which says the OT covenants were carnal, doesn’t hold. As soon as that’s admitted, their position that the NC and OC are substantively different is gone. Of course, that’s the whole reason they put themselves in this position in the first place.

While we’re at it, would the federalists mind explaining to us why, per 2 Corinthians 3, the Holy Spirit is necessary to understand Moses if the Mosaic Covenant is not inherently spiritual? Is Paul superimposing spirituality, after the cross of Christ, back onto the MC? Of course not. This means it is spiritual in nature. Of course that’s exactly what Paul tells us in Romans 7:14. So who should we follow—1689 federalists, or the Apostle Paul? That’s an easy answer.

Further, read WCF 7 and pay special attention to sections 3, 4, and 5, and the movement from one to the other. Westminster doesn’t disagree with 1689 federalists that it is ultimately by Christ alone and his death that we are saved. The Confession states that clearly in sections 3, 4, and 5 of Chapter 7. The point is there is one substance, namely Christ and his benefits, differently administered. Section 3 says, the Lord [made] a second [covenant] called the Covenant of Grace; section 4 says this covenant of grace is frequently set forth in the Scripture by the name of a Testament, in reference to the death of Jesus Christ the testator; section 5 says this covenant was differently administered in the time of the law, and in the time of the gospel. Thus, the same religio-spiritual truths we see most clearly in the NT with the coming and work of Christ as a man are the same fundamental principles which have always been given from Genesis 3:15 and 3:21 forward. Without the shedding of blood there is no remission of sins (Hebrews 9:22 taken from Leviticus 17:11). Amen. Thus, God symbolically exhibited this by slaying an animal in the garden for Adam and Eve. In other words, there is one substance and various administrations of that same substance.

Side Note

Here, I’d like to make a side note. Unfortunately, equivocation and confusion sometimes takes place in these discussions when using the word “substance.” Often, 1689 federalists use it one way while Westminster Federalists use it another. The 1689 Federalist may say something like, “The goat is a shadow; Christ is the substance.” In that sense, we obviously agree; a goat and Christ are different, one being a mere animal and the other the incarnate God. However, this is not how Westminster Federalists use the term. They typically say something like this, “The goat, as a substitutionary sacrifice to be slain is exhibiting the same substance we see in Christ as our substitutionary sacrifice.” In other words, Westminster Federalists often use the term “substance” to refer to the fundamental truth which is exhibited symbolically whereas 1689 Federalists often use “substance” to refer to the distinction between Christ (as antitype) to a goat (as a type)—in which case they are correct in saying that Christ and a goat are not the same. However, because of these different uses of “substance” confusion takes place. This is why definitional clarity is important. No one disagrees that an animal and the Lord Jesus are obviously not the same thing, and that the lamb is but a shadow while Christ is the substance. However, the truths exhibited in a lamb being slain are the same, for substance, as those seen embodied in Christ as the Lamb being slain. In this way there is substantive or substantial agreement.

In the simplest way I can put it: symbolically, there is and even must be substantial or essential agreement. Typologically, however, there is disagreement. I have written about this very important distinction in a paper located here, which I encourage all those interested to read: The Scotsman and Sinai.

Addendum & Some Summary Points

So let me try to be a bit more clear on some, certainly not all, of the stated differences.

- No one argues that animal sacrifices *in themselves* were efficacious to save. No one. So we agree that only Christ ultimately saves.

- We agree that the New Covenant was, with respect to the actual human blood of Christ, inaugurated at the cross.

- We agree that salvation, in its substance, was present in the Old Testament just as it is in the New Testament.

- We agree that the Old Testament is replete with typology; however, I’d argue that Westminster Federalism is more consistent with the necessary implications of this point.

- We agree that there must be some point of duality in the Old Testament in order to make sense of the biblical data.

So where do we disagree?

Where we disagree is in parsing out many of the related details. Westminster says that the Old Testament covenants can be considered from two major perspectives:

- First perspective: The covenants had an outward administration (carnal) and an inward substance (spiritual). This is duality. Not all in or under the administration actually possessed and appropriated the substance. And the same is true today even in the New Covenant.

- Second perspective: The Old Testament narrative, the covenants, and many of their ordinances operated on three levels: (1) carnal, (2) symbolical, and (3) typical/typological.

Where we maintain essential, substantial, or fundamental unity between not only the two testaments and the whole Bible but also within all the covenants is the substance of the first perspective and the symbolical of the second. Really, they are synonymous. This is because the symbolical element, as Fairbairn has said, means that a thing “expressed, by means of the outward rite or action, certain religious views and principles, which the worshipper was expected in the performance of the service to recognise, and heartily concur in. It was the conscious recognition of these views and principles, and the exercise of the feelings growing out of them, for which more immediately the outward service was appointed, and in which its acceptability with God properly consisted.” Likewise, this means that the outward things “were not [merely] outward rites and services of any sort. The outward came into existence merely for the sake of the religious and moral elements embodied in it, for the spiritual lessons it conveyed, or the sentiments of godly fear and brotherly love it was fitted to awaken.” In other words, the whole point of the symbolical is to exhibit the spiritual, or what I have elsewhere called the religio-spiritual. So Westminster locates the “substance” unity in the inward, spiritual, and symbolical elements, while at the same time we recognize that there is not a precise unity when considering a type (lamb) and antitype (Christ). This brings me to my next point.

1689 Federalism maintains that the Old Testament covenants, insofar as I have understood things, were carnal for then-present saints, and, they also believe they were typological, broadly speaking. This means they reject the inward substance of the first perspective and they omit, at least on a practical and emphasis-level and as defining the nature of the covenants, the symbolical element in the second perspective above. Thus, they do not definitively determine the nature of the covenants as being spiritual or possessing a spiritual substance. Therefore, in that respect, they see no essential, substantial, or fundamental agreement between the testaments or the covenants. This is because they focus on the disagreement between type (lamb) and antitype (Christ), saying that an animal is obviously not the same in substance as the God-man Redeemer. Then they, insofar as I can tell, apply this as a paradigm on all the covenants. The major problem here, as I have already stated both above and in my paper, is that there is no typology without inherent then-present spirituality. If you admit the former you are necessarily admitting the latter.

Now, if you have followed what I’ve been saying, then what I’m about to say makes sense. While Westminster agrees with 1689 Federalists that there is discontinuity or disagreement between a lamb, as a type, and Christ, as antitype, it disagrees on at least two points: (1) that this is an/the overriding paradigm to define the OT and its covenants, and (2) that this means there is *no other* essential, substantial, or fundamental agreement. In point of fact, there is such an agreement and it is deeper than type/antitype, namely the spiritual and symbolical.

The symbolical is of chief and paramount importance. Without it, we do not have the ability to rightly govern or delimit our typology. It is, in fact, the basis of typology as both Patrick Fairbairn and Geerhardus Vos argue. I cite both of them repeatedly in my paper above. Likewise, it is this element in particular which establishes the substantial, essential, or fundamental agreement which Westminster maintains.

Thus, the question that needs to be asked is not, “Did animal sacrifices in themselves save?” No one argues that they did. No one. The question, rather, is this: “Did animal sacrifices symbolize any truth that saves?” The answer is yes. So we then can say, confidently and consistently, that we agree with 1689 Federalists: yes, Christ alone saves. And we add, by way of disagreement: the same spiritual truths demonstrated in his New Covenant sacrifice are also exhibited in animal sacrifices by means of the symbolical element. Therefore, we (1) readily recognize the carnal element but do not reduce things to mere carnality; (2) readily admit the difference between a lamb as a type and Christ as antitype; (3) maintain the sole sufficiency of Christ alone; (4) maintain the essential unity and agreement of the covenants, spiritually speaking and symbolically speaking, via the religio-spiritual truths exhibited; (5) ground, delimit, and specify typology, which is most necessary; (6) enable OT saints to engage in meaningful worship via the symbolical element and the spirituality it conveys, which we must not and dare not deny to them; and (7) do justice to the doctrine of God, as being a Spirit and always requiring spiritual worship, and the plain Scriptures which teach that he did, in fact, accept animal sacrifices and was displeased when they were offered mechanistically, i.e. merely in a carnal fashion, contra 1689 Federalism.

Christ’s sacrifice, therefore, was symbolically present, anticipated, exhibited, and efficacious from Genesis 3:21 forward. We must maintain the progress of revelation and redemption. We must not chiefly consider the matter from our perspective today but from the perspective of OT saints then, during the time that they lived. And in that sense, Christ, though not yet temporally come as the God-man Redeemer to shed his blood, was nevertheless comprehended, exhibited, and anticipated trans-temporally in the sacrifices and worship throughout OT in a symbolical-spiritual manner. Note: This does not mean everyone who who engaged in such actually possessed or appropriated the spiritual value. Further, even with the saints, there is no indication they clearly discerned antitypes. So, then, what did they know? There is no reason for us to think that Abel knew that Jesus of Nazareth the God-man would be crucified for his sins. But he did know that God slew an animal for his parents, covered them in its skin, and instituted animal sacrifices for those who would draw near and worship him. Herein we have: substitutionary atonement, covering, forgiveness of sins via the shedding of blood, an innocent victim, the necessity of death to satisfy justice, etc. Now, tell me, are not these very same principles the same which we see in Christ at the cross? Of course they are. There is one way of salvation. Same truths (or substance, if you will), differently administered at different times.

Here’s an exercise for you to prove this point. In Romans 4 Paul tells us that Abraham believed the gospel and was justified by faith. He references from Genesis 15. Have you ever looked at what the content was of that gospel that Abraham believed? It’s not, “Jesus died for you sins, rose again, and ascended into heaven, and if you confess with your mouth that he is Lord, you will be saved.” All that we are told in Genesis 15:5-6, indeed all that Abraham had, as far as we can see from Scripture, is this: “And he [the LORD] brought him forth abroad, and said, Look now toward heaven, and tell the stars, if thou be able to number them: and he said unto him, So shall thy seed be. And he believed in the Lord; and he counted it to him for righteousness.”

How is that the gospel? (By the way, the wilderness generation also had the gospel preached to them per Hebrews 4:2—do the same exercise and you’ll notice the same thing, namely that what was revealed and preached to them as “the gospel” is not, in its delivered form, the same as something like 1 Timothy 1:15—but it is the same in substance. And this is the point.)

Let me close with a quote from Fairbairn to both answer the question and prove that everything I have been saying is true and most necessary. Here’s Fairbairn:

It would seem as if, after the stirring transactions connected with the victory over Chedorlaomer and his associates, and the interview with Melchizedek, the spirit of Abraham had sunk into depression and fear; for the next notice we have respecting him represents God as appearing to him in a a vision, and bidding him not to be afraid, since God Himself was his shield and his exceeding great reward. It is not improbably that some apprehension of revenge on the part of Chedorlaomer might haunt his bosom, and that he might begin to dread the result of such an unequal contest as he had entered on with the powers of the world. But it is clear also, from the sequel, that another thing preyed upon his spirits, and that he was filled with concern on account of the long delay that was allowed to intervene before the appearance of the promised seed. He still went about childless; and the thought could not but press upon his mind, of what use were other things to him, even of the most honorable kind, if the great thing, on which all his hopes for the future turned, were still withheld? The Lord graciously met this natural misgiving by the assurance, that not any son by adoption merely, but one from his own loins, should be given him for an heir. And to make the matter more palpable to his mind, and take external nature, as it were, to witness for the fulfilment of the word, the Lord brought him forth, and, pointing to the stars of heaven, declared to him, “So shall thy seed be.” “And he believed in the Lord,” it is said, “and He counted it to him for righteousness.”

This historical statement regarding Abraham’s faith is remarkable, as it is the one so strenuously urged by the apostle Paul in his argument for justification by faith alone in the righteousness of Christ. And the question has been keenly debated, whether it was the faith itself which was in God’s account taken for righteousness, or the righteousness of God in Christ, which that faith prospectively laid hold of. Our wisdom here, however, and in all similar cases, is not to press the statements of Old Testament Scripture so as to render them explicit categorical deliverances on Christian doctrine—in which case violence must inevitably be done them—but rather to catch the general principle embodied in them, and give it a fair application to the more distinct revelations of the Gospel. This is precisely what is done by St. Paul. He does not say a word about the specific manifestation of the righteousness of God in Christ, when arguing from the statement respecting the righteousness of faith in Abraham. He lays stress simply upon the natural impossibilities that stood in the way of God’s promise of a numerous offspring to Abraham being fulfilled—the comparative deadness both of his own body and of Sarah’s—and on the implicit confidence Abraham had, notwithstanding, in the power and faithfulness of God, that He would perform what He had promised. “Therefore,” adds the apostle, “it was imputed to him for righteousness.” Therefore—namely, because through faith he so completely lost sight of nature and self, and realized with undoubting confidence the sufficiency of the divine arm, and the certainty of its working. His faith was nothing more, nothing else, than the renunciation of all virtue and strength in himself, and a hanging in childlike trust upon God for what He was able and willing to do. Not, therefore, a mere substitute for a righteousness that was wanting, an acceptance of something that could be had for something better that failed, but rather the vital principle of a righteousness in God—the acting of a soul in unison with the mind of God, and finding its life, its hope, its all in Him. Transfer such a faith to the field of the New Testament—bring it into contact with the manifestation of God in the person and work of Christ for the salvation of the world, and what would inevitably be its language but that of the apostle: “God forbid that I should glory save in the cross of the Lord Jesus Christ,” — “not my own righteousness, which is of the law, but that which is of God through faith.”

Super good, brother!

Thank you, brother. Your critique is insightful, and your follow-up point about semantics is also, insofar as I can see, relevant. There is far too much splitting of hairs and tautology being engaged in by 1689 Federalists, ad hoc formulations to distinguish themselves from Westminster. Denault does this in his book, but it can be easily missed if one is not paying attention. He maintains the visible/invisible church distinction conceptually, but he changes things terminologically by using the words “man’s view/God’s view.” In other words, it’s a semantic, *not* a substantive difference. I’m increasingly convinced it’s the same thing with their whole partial revelation approach. They recognize they must have the substance of Christ present but they refuse to allow it to be a part of the covenants. Yet that’s exactly where the revelations were made, historically speaking, and recorded, biblically speaking. I may write up another post on some of these things.

Cody, I will respond to the main article as soon as I get some time, but can you please elaborate on your comment about the visible/invisible church distinction? The idea that the visible church is merely man’s fallible perspective of the church, which consists of the regenerate alone and is known perfectly by God (invisible church), rather than an external covenant relationship with God, is a substantive difference. Have you read John Murray’s criticism of James Bannerman on this point, for instance?

Hey Brandon, thanks for your comment and interest. I await your response. As for my comment about the visible/invisible church distinction: when I read Denault—which was some time ago now—I recall him retaining the concept but using different terms, i.e. “man’s view/God’s view” instead of “visible/invisible church.” I disagree that visible/invisible church + administration/substance of covenant + covenant community/elect is a substantive difference from man’s view/God’s view. The concepts are the same. The terms are different. Perhaps the emphases may also be different.

Now I grant that 1689 Federalism intends to mean by “man’s view” those who are not elect, and, being that the NC is made with the elect alone, this means they were never in covenant, and therefore never had a covenant relationship with God, not even a Westminster-esque “external covenant relationship with God.” The issue is what is meant by that last phrase, conceptually, is something I don’t expect you would disagree with, i.e. hypocrites, carnal persons, and reprobates participating in the life of the church and under her ordinances yet remain unregenerate and unbelieving. In other words, conceptually, Westminster would agree with 1689 Federalism that such persons were never (truly) in covenant, when speaking of the substance of the covenant; while there was an attachment, it wasn’t spiritually vital. But Westminster would disagree in saying that they were in covenant externally (as you say), when speaking of the administration.

So you all are saying from God’s view, the church is the elect. Brother, who would disagree? Yet from man’s view, i.e. the visible church, we see the church also includes the non-elect. Of course this has always been the case. Denault admits in footnote 85 on p.94 that man’s view/God’s view is “simply the historic articulation of the visible/invisible church distinction as a difference in viewpoint.” What I found particularly telling is the complete absence of exegesis in Denault of passages which are commonly used to prove the mixed nature of the church and covenant (administratively), i.e. Romans 9:6 and Ch. 11, John 15, Hebrews apostasy passages, Revelation churches, Demas, Diotrephes, parables of the soils and of the fishnet and of the wheats/tares. I have his entire book marked up from beginning to end. Perhaps one day I’ll write a critique/review of it.

I have not read Murray’s criticism of Bannerman. You’re welcome to share that.

Thank you for the response. Sorry for the delay. I did not receive an email notification of your reply.

Denault likely did not deal with all of those texts because the focus of his book was historical summary, not exegetical. If you want my opinion of those texts, see

https://contrast2.wordpress.com/2016/08/27/they-are-not-all-israel-who-are-of-israel/

https://contrast2.wordpress.com/2015/02/08/the-olive-tree/

https://contrast2.wordpress.com/2015/06/12/hebrews-10-john-15/

Setting aside the word “substantive,” there is a *meaningful* difference between saying that a hypocrite is in covenant with God (from God’s perspective) and saying that a hypocrite only appears to be in covenant with God (from man’s perspective).

For Murray’s critique, see his essay “The Church: Its Definition in Terms of ‘Visible’ and ‘Invisible’ Invalid” in Volume I of his Collected Writings. He also wrote about it in “The Theology of the Westminster Confession of Faith,” found in Volume IV as well as his book “Christian Baptism.” Here are some excerpts https://contrast2.wordpress.com/2016/12/05/john-murray-the-baptist-vs-james-bannerman-the-presbyterian-on-the-church/

See also https://contrast2.wordpress.com/2019/02/11/19th-century-scottish-presbyterian-criticism-of-bannermans-visible-invisible-churches/

https://contrast2.wordpress.com/2015/01/28/church-membership-de-jure-or-de-facto/

https://contrast2.wordpress.com/2019/03/05/the-french-reformed-understanding-of-the-visible-invisible-church/

https://contrast2.wordpress.com/2016/05/14/a-brakel-on-the-visibleinvisible-church/

https://contrast2.wordpress.com/2019/03/07/hodges-baptist-understanding-of-the-visible-invisible-church/

(Note: see the explanation of the kingdom parables in the above excerpts).